October is unfortunately for a lot of people the beginning of cold season. Regardless of the fact that I know the air recirculation and filtering on British Airways is highly effective, I will probably wear a mask for the majority of my upcoming flight to Heathrow, simply because sitting in one spot for eight hours has never struck me as a particularly healthy place to be.

In the eighteenth century, of course, we didn’t understand that disease was the result of viruses and bacteria. People thought contagions were caused by ‘bad air’ (the word malaria literally means ‘bad air’). We weren’t entirely wrong, were we? We just didn’t know what made the air bad; in general, we thought it was miasmas: rotting vegetation and open cesspits and things of that nature. But regardless of what we thought caused it, illness was commonplace and unavoidable. And unless you felt like you were at death’s door, you just got on with it.

In my last newsletter I wrote about humoural medicine. It was still the most widely used method of ‘diagnosing’ illness. But apart from humoural theory, people had a home pharmacopeia of remedies that were based on their perceived effectiveness. I wrote ‘perceived’ because there isn’t really any way to assess how well they worked or didn’t… but just recently in the United States an independent advisory committee to the US Food and Drug Administration agreed that phenylephrine, a popular ingredient in many over-the-counter allergy and cold medicines, is ineffective in oral preparations. Yet we have been buying cold-relief products containing phenylephrine for years, because we perceived that they work.

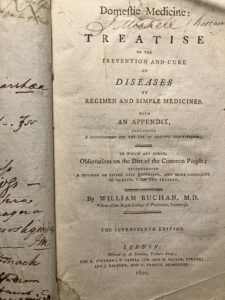

Most households probably had some sort of layman’s medical text on hand. My copy of William Buchan’s Domestic Medicine, or, A Treatise on the Prevention and Cure of Diseases by Regimen and Simple Medicines, was printed in 1800 and is the seventeenth edition — there were many subsequent editions. It contains a lot of the same advice that your own doctor would advocate today. However, many of the ‘simple medicines’ aren’t at all familiar.

In the eighteenth century we thought that colds were caused by ‘obstructed perspiration’. The theory was that provoking a gentle sweat was the trick to getting over a cold. Putting the patient to bed when symptoms first appeared, keeping him warm, and limiting his diet to light fare and ‘warm, diluting liquor’ were the recommended regimen. By ‘liquor’, Buchan doesn’t mean alcohol. He warns, ‘Many attempt to cure a cold, by getting drunk: but this, to say no worse of it, is a very hazardous experiment. No doubt it may sometimes succeed, by suddenly restoring the perspiration; but when there is any degree of inflammation, which is frequently the case, strong liquors, instead of removing the malady, will increase it. By this means a common cold may be converted into an inflammatory fever.’

After an initial day in bed, the recommendation was for the patient to resume gentle activity if they felt well enough. If the cold didn’t respond to such treatment, or was accompanied by fever and a rapid pulse, then the practitioner might proceed to bleeding and applying a blistering plaster to the patient’s back, to cool the pulse and draw off the excess of phlegm.

Buchan is talking about treating the cause of the cold, as it was understood. He says little about treating the symptoms.

The personal medicine chest thought to have belonged to Lord Nelson contained several medications that might have been used to treat cold symptoms. Camphor and Friar’s Balsam could both be added to a vapor bath to relieve congestion, and Friar’s Balsam could also be used as a cough remedy. Incidentally, you can still buy Friar’s Balsam, and syrup of squills (which the medicine chest did not appear to contain) is still used in commercial cough mixtures as an expectorant. Spirits of Sal Volatile was a distillation of what we would call ‘smelling salts’. Inhaling them might also relieve congestion. Salts of Hartshorn, a related preparation, could be used in a ‘sweating draught’ to try to provoke the gentle perspiration thought to cure colds. Lavender might be used for bronchial congestion.

Nelson was fairly abstemious, but I imagine more than a few naval officers treated a cold with a toddy, a combination of rum, hot water, and sugar. It might not have helped the cold, but it undoubtedly made him feel better!

I’ll leave you with a comforting recipe, a modern take on a hot toddy. Dr Buchan almost certainly would not approve, but one can’t hurt… right?

From Forgotten Drinks of Colonial New England by Colin Hirsch

Hot Buttered (Maple) Rum

2-3 cardamom pods

1 pat of unsalted butter (cultured butter works especially well)

a few slices of peeled fresh ginger

1 tsp of light brown sugar, or more to taste

pinch of orange zest, or orange twist

pinch of nutmeg

pinch of cinnamon, or a cinnamon stick

1 dram of (maple) rum, to desired strength

hot water

a few drops of vanilla (optional)

Add cardamom pods to bottom of a tall mug and muddle slightly with a pestle or other blunt kitchen tool. Add butter, ginger, sugar, orange zest, and spices. In a separate mug, combine rum and hot water and then pour over spice mixture. Stir to dissolve butter and sugar, add a few drops of vanilla if desired and serve.

I found this post fascinating! I hadn’t realised that so many people would have had medical books like the one by William Buchan that you have. I probably assumed that in those days most people wouldn’t have been able to read so any medical knowledge they had would have come through word of mouth and only the wealthy would have owned books. I love looking at old books as I feel it really helps us understand how people used to see the world and it helps me imagine what it would have been like to live in the olden days.

Hi Charlotte,

Thank you for pointing that out! You’re correct that in households where people couldn’t read, they relied on clinics, apothecaries, and folk healers; they had no choice. If your family was just getting by, you didn’t consult any of these options until it got critical, either; you had to pay for the service or at least for the medicine, and that might mean your family didn’t eat or buy fuel for the fire. Dr Buchan was useless for people who couldn’t read, but middle- and merchant-class households would have likely have had some kind of family medical book, be it Dr Buchan or a book of hand-written remedies collected over generations.

Great comment! Thank you!

I’m so sorry it has taken me so long to write back!

In the olden days did people like Dr Buchan have to prove that their remedies really worked? I’m sure that Dr Buchan was very conscientious and only recommended treatments and remedies if he really believed in them but I was wondering if doctors or apothecaries ever tried to trick people into buying medicines that didn’t work? I remember one of my teachers telling us that these days there are lots of rules that drug companies have to follow and they aren’t allowed to sell medicines until they have demonstrated they are safe and effective so in a way there is quite a lot of consumer protection. I just wondered if in the olden days people may have been quite vulnerable to being taken advantage of by apothecaries, especially if they couldn’t read or write, as they wouldn’t really have known if the remedy they were buying was going to help them.

I hope that all doctors and apothecaries were kind and trustworthy!

Hi Charlotte — the Royal Colleges of Physicians in London and Edinburgh licensed physicians, and many apothecaries were in fact trained equally rigorously; although they couldn’t claim to be members of one of the Royal Colleges of Physicians, they could diagnose and treat illness, and the treatments they sold were regulated. That doesn’t necessarily mean that all apothecaries, or all physicians, for that matter, were trustworthy, and many medicines that were used in the eighteenth century were questionable. They were legitimate, but whether they were efficacious is debatable. Some treatments went back to Galen, who was a Greek and Roman physician in the second and third centuries AD. (Much of medical theory in the eighteenth century was still based on Galen.) Now, if you were a particularly credible person who would buy a miracle mixture from a street huckster, you were probably going to be cheated, because nobody regulated that stuff and it might have been nothing but urine mixed with clay and gin! But I have to believe that most practicing healers, whether they were accredited or folk healers, were invested in helping people get well. (Dr Buchan was a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh.)

Thank you very much for helping me understand what things were like in the eighteenth century. The street hucksters that you mention sound really unscrupulous because I’m guessing that they knew that what they were selling wasn’t going to help people get better so they were taking advantage of people and cheating them. I guess that well-meaning apothecaries sometimes sold people medicines that didn’t really work but to me that isn’t nearly as bad as what these street hucksters used to do because the apothecaries really did believe that their medicines were effective and they really did want to help people whereas the street hucksters knew that what they were selling wasn’t going to help anyone get better so they were deliberately tricking people and cheating them which is awful!

Do you think that sometimes medicines could actually make people more unwell? I feel so sorry for the poor people who were tricked into drinking urine! How disgusting!!! Do you think people would have realised they had been cheated as soon as they started to drink the mixture? I dread to imagine how smelly it must have been!

There were some legitimate medicines that may have been more harmful than helpful. Calomel, which was a preparation of mercury, was used until the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries to treat a number of things. Mercury was also used in ointments, as well as orally, to treat syphillis. We know that mercury is poisonous, and undoubtedly a number of patients died of mercury poisoning and not of whatever the physician was trying to treat. Louisa May Alcott, the nineteenth-century poet and novelist, was sure that she had been poisoned when she was given calomel for a fever during her service as a nurse during the Civil War. But it was true then, and it is true today, that what is poisonous in large doses can be medicine in small doses. (I’m not sure that mercury is one of those things, but I’m not a chemist.)

Mercury as a treatment is one of those medicines that went back to the ancient Greeks and Romans. I try to be charitable to eighteenth-century physicians; they didn’t know what germs were, and their understanding of molecular science was primitive. But despite that, people did get well under their care, even if we can’t prove whether it was medicine or chance that cured them.

I can completely see that back in the eighteenth century it would have been much harder for people to establish how effective medicines were and I guess that lots of people were superstitious and maybe didn’t think about things quite as rationally as maybe a scientist or a doctor would today. These days we can carry out large clinical trials whereas I guess that in the olden days a lot people probably believed things on the basis of anecdotal evidence that hadn’t been examined critically and they probably attributed symptoms to the wrong causes and targeted the wrong things when they were trying to treat illnesses. I really like how you try to be charitable to doctors and apothecaries who lived in the eighteenth century as to me it is people’s intentions that are most important when we judge them and it isn’t fair to criticise people for getting things wrong if they tried their best and were motivated by the right things like trying to relieve patients’ suffering. I feel that history teaches us to be humble and open-minded because we can see how much our knowledge and understanding have advanced over the centuries and we have found that even the greatest thinkers were not always right about things so we should always be open to the possibility that our theories and beliefs are not quite right and may need to be revised in the future when new evidence comes to light.

Please forgive me for asking another question but I just wondered if street hucksters ever used to get in trouble if the fake medicines they sold made people ill? My impression is that these days doctors have to be quite careful because they have a duty of care to their patients and they could actually be stripped of the right to practise and maybe even prosecuted if they cause people harm (even if they were just trying to help) but I’m curious what things were like in the eighteenth century. If you bought a fake medicine from a street huckster and you discovered you had been cheated was there anything you could do or did you just have to accept that you had been tricked? I guess that sometimes people may have been too embarrassed to confess that they had been cheated by a street huckster but I was thinking that some people would probably have had a really strong sense of injustice and would have wanted to get their own back on the person who had tricked them, especially if they had bought something really disgusting like urine! If someone tricked me into drinking urine I would be really angry and upset but I would also be really embarrassed and I probably wouldn’t want anyone to find out that I had been such a fool, especially if I thought that people would laugh at me and make fun of me.

They might have been arrested, if they could be caught. The authorities did regulate legitimate medicines (and poisons). But these types of people were usually itinerants–they moved from town to town or parish to parish, showing up on market day, unloading as much as they could on the unwary, and then disappearing. And by the time someone complained, they were long gone.

I imagine that their ‘medicines’ were mostly alcohol–gin was cheap–disguised with other substances to make it taste medicinal. In my example I chose clay (or chalk, or peat, or any kind of earth, depending on where you were) and urine because both were plentiful, but I suppose it could be anything that was easily available. And nobody expected medicines to taste good! Consider what the person told you it could do: they usually claimed that these preparations would cure anything from a cold to scrofula to dropsy! And I suspect you’re right, some folks, when they found that they’d been cheated, wouldn’t have let anybody know that they were so easily fooled.

Thank you very much for helping me with my questions! It hadn’t occurred to me that people perhaps wouldn’t have been all that suspicious if a potion they drank tasted revolting because they were maybe used to medicines tasting horrible and if they believed that a potion would make them better then they might have been prepared to drink it even if it tasted like urine and made them feel sick! Do you think it would have been the same if a potion was very smelly? I had thought that if a street huckster sold a potion containing urine it would have been so smelly that people would have known that it wasn’t a real medicine and wouldn’t help them get better but maybe they wouldn’t necessarily have realised if they were used to things being smelly?

I am so sorry for asking so many questions!

I wasn’t there, of course, but I imagine that these concoctions didn’t taste or smell like anything identifiable. They might have been flavoured with something bitter, like dandelion or dock leaves or gentian root (which actually did have medicinal properties when used properly, but given the nature of the transaction, I doubt that was a consideration) to disguise whatever the base of the mixture was, whether it was bad gin, pond water, or something else.

The transaction probably depended largely upon the impulsivity of the buyer. Medicines sometimes made outrageous claims, so people might not be suspicious of a product that would (it claimed) cure toothache, make your hair grow, and improve your virility all at once! I doubt that people who were truly unwell bought these things, although there’s really no way to know.